One of the books I am currently reading is Peter Frankopan’s The Silk Roads: A New History of the World. I have just begun the work and find it both interesting and irritating. Interesting in that it has much to impart to me and irritating in that too much of the information imparted is highly superficial. Fortunately, there are notes but, alas, they are endnotes rather than footnotes.

Additionally, the information contained in the notes is sparse. The upshot of the foregoing is that when I come across a provocative morsel of information, which occurs with frequency, I am compelled to leap headlong down the proverbial rabbit hole in search of enlightenment. For instance, the following tantalizing appetizer appeared on pages 8-9 of Mr. Frankopan’s tome:

“At Ai Khanoum in northern Afghanistan – a new city founded by Seleucus – maxims from Delphi were carved onto a monument, including:

As a child, be well behaved.

As a youth, be self-controlled.

As an adult, be just.

As an elder, be wise.

As one dying, be without pain.”

Being reasonably educated, I may claim general familiarity with Afghanistan, Seleucus, one of the Diadochi who fought for control of Alexander the Great’s empire after his death, and things Delphic; however, I may not claim any familiarity with Ai Khanoum or the particular Delphic maxim cited. Therefore, I immediately looked to the referenced endnote in hopes of being further educated about each of the foregoing as the main text provided only the tease outlined above and nothing more. Alas, a review of the endnote (number 24 in chapter 1) revealed that it only cited two works, one in French which suggested that it was apparently the repository of the original Greek inscription and the other apparently the repository of the English translation of the Greek inscription by F. Holt. The endnote provided no commentary to sate my appetite for context or illumination regarding the city, its founding, or the Delphic maxim.

Immediately putting the book aside, I fired up the mystical engine that facilitates my instantaneous access to sources of knowledge once unfathomable to my imagination, and within minutes I am able to begin to sketch out the missing context for the above tease from Mr. Frankopan.

Let’s begin our tumble down the rabbit hole with an anecdote recorded in an article appearing on the Biblical Archeological Society Website entitled Alexander in the East, which was written by Frank Holt, the translator of the Greek inscription cited in the note above:

“On a royal hunt in a remote corner of his realm [in 1961], King Muhammad Zahir Shah of Afghanistan spotted a strange outline in the dry soil between two rivers. Looking down from a hillside at this confluence of the Amu Darya (ancient Oxus) and Kochba rivers, the king could see traces of a well-planned ancient city: A wall and defensive ditch stretched from the hill to the Oxus, broken only by a gateway leading to the main street inside the settlement. The shapes of many large buildings bulged underneath the thin carpet of dirt, and at least one Corinthian column rose up like a signpost of Hellenistic civilization. Here, at last, was Alexander’s elusive legacy in the East.”

And what was this elusive legacy of Alexander’s in the East? Well, to answer this, here we do well to lift generously from another scholar, Jeffrey Lerner, and his article entitled Alexander’s Settlement of the Upper Satrapies in Policy and Practice, which provides ample context for the significance of King Muhammad Zahir Shah’s find:

“Alexander’s plans for maintaining his authority over the region involved the stationing of troops in a system of strategically placed cities and fortifications. A manifestation of Alexander’s authority that was particularly directed at the Upper Satrapies was the founding of settlements denoted by Greek authors as πόλις and by Roman authors as urbs. Justin, for example, notes that Alexander established seven cities in Baktria and Sogdiana. The problem with identifying Alexander foundations is not knowing the number of cities that he or his successors founded. To date no site in Central Asia dating to the Hellenistic period has yielded an inscription bearing its name, whether in Greek or in any other language. For example, there are a number of cities whose foundations are attributed to Alexander, but apart from their names, there is precious little else known about them.”

Lerner goes on in his article to discuss Aï Khanoum, which had been the object of archaeological survey under the direction of French archaeologist Paul Bernard from 1965 until the 1979 Soviet invasion of Afghanistan:

“One particularly illusive foundation that has attracted a great deal of attention is that of Alexandreia on the Oxos, which Ptolemy places in Sogdiana, but whose whereabouts remain highly controversial due to Ptolemy’s placement of the city in relation to the rivers Oxos and Iaxartes, μεταξὺ δὲ καὶ ἀνωτέρω τῶν ποταμῶν. This prompted Bernard to remark that the difficulty of reconciling the whereabouts of the city with its name is that it supposedly existed along the river Oxos, because as a general rule cities named after rivers are located directly on their banks. Apparently, Ptolemy erred in combining data on two different cities in the same description. Nonetheless, several suggestions have been made as to its location. One holds that Alexander had founded the city at Termez on the north bank of the Oxos and, following its destruction by nomads, was refounded by Antiochos I as Antioch-Tarmita, but was subsequently refounded by the Greek-Baktrian king Demetrios I as Demetrias in the second century BCE. The discovery of the site of Aï Khanoum in northeastern Afghanistan south of the river Oxos in Baktria led Bernard to conjecture that this region of Baktria was actually part of Sogdiana. To make this reconstruction work, he further speculated that upon the conquest of Marakanda by nomads, Aï Khanoum became the country’s capital with the Kokcha acting as the border between Baktria and Sogdiana. Rtveladze has argued that Kampyrtepa was Alexandreia Oxiana. Finally, the fortress of Takhti Sangin in modern Tajikistan on the north bank of the Oxos situated between Ai Khanoum and Termez has also been proposed as the ancient city. The site contains the so-called Oxos Temple in which an altar dedicated to the river god Oxos by a certain Atrosokes was recovered.”

A few lengthy paragraphs from Lerner are in order as to why Alexander would have settled some of his men on the farthest fringes of his conquests and how those men were selected and reacted to their selection:

“As a rule, Alexander employed a settlement policy in the regions of the far eastern corridor of the empire as one method of controlling these subjugated states. This practice, like many others that Alexander followed, was initiated by his father, although of course in Alexander’s case on a much larger scale. The role that cities played in achieving this goal was two-fold. First, many were so hastily constructed – literally in the matter of days – that they appear to have been little more than military colonies with names given them to connote a sense of grandeur, like ‘Alexandreia.’ Such was the case of Alexandreia Eskhate that served as no more than a frontier post. On the other hand, Alexander’s propensity for renaming existing cities, usually after himself, seems to have enjoyed longer lasting success, like Alexandreia Arachosia/Alexandropolis, and Alexandreia Areia among others. The key to understanding Alexander’s achievement with this policy was the practice of creating colonies of heterogeneous populations, consisting in the vast majority of cases of indigenous peoples and Greek mercenaries, and only rarely Makedonians. Aside from serving as the king’s direct agents in the satrapies, these settlements also had the benefit of allowing Alexander to rid himself of dissatisfied elements in the army by stationing them in remote places as punishment for their insubordination. Indeed prior to the rebellion of 325 BCE, Koenos states emphatically that Alexander had left behind in Baktria Greeks and Makedonians who had no wish to remain. As a matter of course retired soldiers received land and quite likely economic support to set up a farm. The local population, however, by all appearances did not fare as well as their Greek and Makedonian counterparts. This is especially true in the case of a captured population, such as those who were taken prisoner at the Rock of Ariamazes. The majority of those who had surrendered were given to the newly arrived settlers as slaves of the six towns situated near Alexandreia Margiana. No matter how imperfect this policy of colonizing the conquered regions in the Upper Satrapies may have been in hindsight, it did provide some measure of control, while also safeguarding communication routes, and the king’s borders. The method of founding new cities, deploying garrisons in large old cities, coupled with the creation of military colonies was to a degree based on Alexander’s policy of integration, even if it was compulsory. Yet the garrisons appear to have been generally small, ranging from a few dozen to several hundreds. The overall effect of this policy was that it served as the basis of contact between peoples and the resulting cultural interaction that might otherwise have not occurred.

Throughout his campaign in the further east Alexander established military settlements that later became cities and renamed cities after himself, though the locations of each remains controversial. Yet the veterans he left behind were hostile to his intentions and revolted in 325 and 323 BCE. For those who rebelled wanted no part in living on the fringes of the known world. Rather they passionately desired to return to a polis lifestyle replete with Greek institutions and a citizenry who shared similar values as opposed to the drab settlements in which they found themselves as just one constituent body in an otherwise mixed population. The so-called cities that Alexander constructed in less than three weeks could in no way resemble cities like Aï Khanoum of the future, for they were the products of the next period. Certainly, the numbers of these veterans had seriously declined especially after the revolt of 323 BCE, in which they found themselves a dwindling minority. They were aliens in an alien world. While they helped conquer this part of Alexander’s kingdom, they had no desire to rule it. Nonetheless, the arrangement that Alexander had established by the time of his death generally held firm as Makedonian supremacy throughout the empire existed without any serious challenges, save among the Makedonian generals themselves. The wars of the Diodochi had little effect on the indigenous populations of the empire as this was left to those charged with administering it, particularly the satrapies in the further east.”

All the foregoing suggests, therefore, that Aï Khanoum, attested in the archaeological survey as a splendid Hellenistic city in its heyday (more on this below), was likely “founded” by Alexander in a perfunctory manner with, at best, slightly disaffected veterans from his campaigns. Whether it was founded from scratch or on a pre-existing village that was simply renamed is unclear to me at this stage of my reading. However, it is clear, that after Seleucus acquired his mastery of much of Alexander’s empire, including the Upper Satrapies which included Aï Khanoum, the city acquired a mint (always of interest to this numismatist) and he invested in the city’s development.

At this point, we may return to the ever so brief snippet from Mr. Frankopan which began this entire journey, as the larger context is now set, for the more specific illumination which is now to be provided by an extract from the earlier article cited by Mr. Frank Holt:

“The Greek founder of this colony [Ai-Khanoum], which may have been called Alexandria Oxiana, was a man named Kineas, whose fourth-century B.C. shrine and tomb stood in the heart of the city. Kineas may have been one of Alexander’s soldiers, sent to settle this strategic fortress on the frontiers of Bactria. There are indications of an attack on the site soon after Alexander’s demise, perhaps part of the disturbances that took place when Greek settlers attempted to abandon Bactria. Fifty years later, under the aegis of the Seleucid dynasty, a major building phase began. True to Greek cultural traditions, the later citizens of the city enjoyed a large theater, a gymnasium with a pool, and quantities of olive oil and wine. Papyrus for writing was transported from Egypt.

These ancient Greeks built large, luxurious private homes and a great sprawling palace. Their Greek names and political titles appear on tombstones and government records. To preserve Greek values in this alien land, an Aristotelian philosopher copied the Delphic Maxims in Greece and carried them all the way to Bactria. An inscription found at Ai Khanoum explained to the colonists that these maxims were the wise counsel of earlier Greeks as codified by priests at the sacred site of Delphi. Their closing lines convey the idea of this Hellenic creed ‘blazing from afar’:

As a youth, be self-controlled.

As an adult, be just.

As an elder, be wise,

As one dying, be without regrets.”

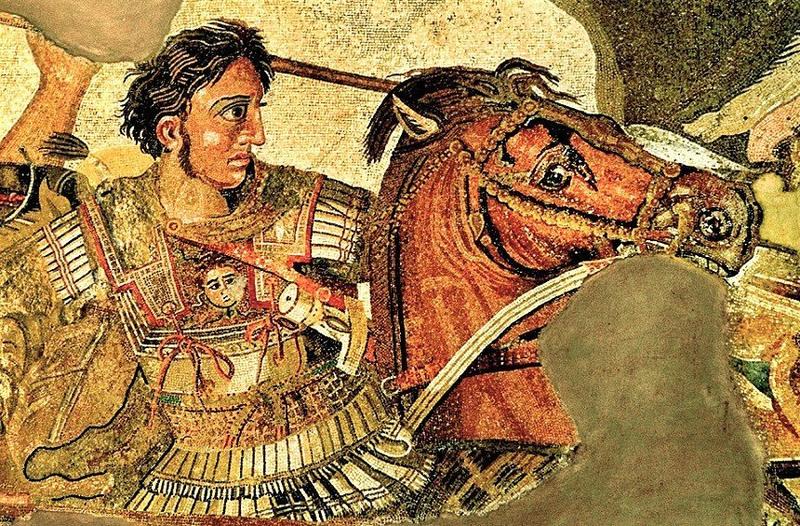

Mr. Holt makes passing reference above to how the Delphic maxims inscribed on the funerary monument, illustrated above, found there way to the city and the shrine dedicated to Kineas. I note that the funerary monument includes the following inscription on it, explicitly explaining how the Delphic maxims came to be there:

“These wise commandments of men of old- Words of well-known thinkers – stand dedicated in the most holy Pythian shrine. From there Klearchos, having copied them carefully, set them up, shining from afar, in the sanctuary of Kineas.”

Thus, a gentleman name Klearchos traveled from the holy Phythian shrine, the temple of Apollo at Delphi, where he copied the maxims, to Ai Khanoum, to have the maxims engraved on a funerary stone. As to the Delphic maxims, the words of well-known thinkers, that would be another entire post!

Finally, if you have the time and access to the Scientific American, I recommend the following article for more background on this city and its archaeological survey:

Bernard, Paul. “An Ancient Greek City in Central Asia.” Scientific American, vol. 246, no. 1, 1982, pp. 148–159. Another recommended article is linked in the button below and explores, in depth, the literature through 2015.

I also recommend the following American Numismatic Society lecture by Michael Alram (“Money and Power in Ancient Bactria”) which surveys the numismatic history of Bactria, and in a number of places, discusses the coinage found at Ai Khanoum:

Recommended Reading: